Rubber + Wood

About the Photographs

The rubber tree, a native of South America, was brought to Southeast Asia following the advent of vulcanization in the early 1800’s. These photographs of para rubber trees and activities and labors associated with the crop were made in southern Thailand where the tree is commonly found in sea level coastal areas as well as low mountain jungle. The tree is tapped to produce latex to which a mild acid is added to initiate coagulation. In the province of Nakhon Si Thammarat, small local producers bring their latex to the simple facility of a neighbor who will accept their trees' production and process the latex to rubber sheets that are then taken to market. Depending on the elevation where the plantation is located, a tree will prove economically viable for a good 20 or more years after which it is logged for its hardwood. "Economically viable" is key to how long the tree will stand. Even if a tree is younger and producing a steady supply of latex, if the rubber can't be marketed for a good price, farmers will cut down the trees to put in another more quickly growing cash crop.

On flat terrain at low elevations, the logs of the felled trees can be removed with heavy equipment. At higher elevations in steep and rugged jungle terrain, elephants are needed to haul out the logs. There are multiple roles involved in making all this happen. The small farmer taps the trees and sends the latex to a local processor. The processor makes and sells the rubber sheets. When the trees stop producing or are no longer economically viable, the land owner contacts someone to remove the trees. Depending on where the trees are you'll need different resources to get the parawood to the mill. In the case of many of these photographs, the trees were growing in low jungle. To remove them you need an elephant or two, an elephant owner, an elephant handler, loggers with chain saws, a crew to make the big logs into small logs and load the wood to a truck that will haul it all to the sawmill, crews of workers to make the logs into boards and, when appropriate, pressure treat that wood, etc., then other trucks to move the pallets to a transport such as an ocean-going ship to get the milled wood to its final buyer. In the case of the parawood mill in these photographs, the majority of the wood is shipped to China where it can be made into furniture.

To my eyes there is beauty in the role of the elephant in this process. They are magnificent and intelligent creatures. There appears genuine affection between the animals and their handlers. A water source of some sort is required and provided for the animals, and they are rested during the work day. At the end of the day, depending on the job the elephant or elephants return to the owner from whom they were leased. Judging from what I’ve seen, once back home, they rest comfortably and eat well.

Rubber tree seed, southern Thailand, 2015

Small rubber tree plantation, southern Thailand, 2015

Morning tapping latex from rubber trees, southern Thailand, 2015

Slow drip of latex into collection pot, southern Thailand, 2015

Vessels of latex coagulating after addition of a mild acid, southern Thailand, 2015

Rolling out of coagulated latex, southern Thailand, 2015

Lifting coagulated latex for extrusion as sheets, southern Thailand, 2015

Extruding coagulated latex into sheets, southern Thailand, 2015

Hanging latex sheets to dry, southern Thailand, 2015

Latex sheets hung to dry, southern Thailand, 2015

Walking along low mountain jungle rubber plantation, southern Thailand, 2015

Elephant with handler working on moving felled trees to lower ground, southern Thailand, 2015

Elephant handler resting at abandoned house during a rainy day of work, southern Thailand, 2014

Elephant and handler walking in tandem through tangled drainage, southern Thailand, 2014

Elephant straining against chains dragging a log, southern Thailand, 2015

Clearing logs from mud and rocks during downpour, southern Thailand, 2014

Young men waiting to haul cut log sections to lower ground for transport by truck, southern Thailand, 2014

Elephant and handler, southern Thailand, 2015

Elephants returning to work following a lunch-time break for cool-down, rest, and water, southern Thailand, 2015

Logger taking down a rubber tree, southern Thailand, 2015

Experienced elephant positioning itself to the side of a log being pulled to river below, southern Thailand, 2015

Elephants dragging logs felled on higher ground down drainage to staging area, southern Thailand, 2015

Workers cutting logs to smaller pieces for transport while elephant rests and snacks, southern Thailand, 2015

Workers cutting logs to smaller pieces for transport while elephant rests and snacks, southern Thailand, 2015

Burmese migrant worker hauling log section to transport truck, southern Thailand, 2015

Burmese workers loading logs to transport truck, southern Thailand, 2015

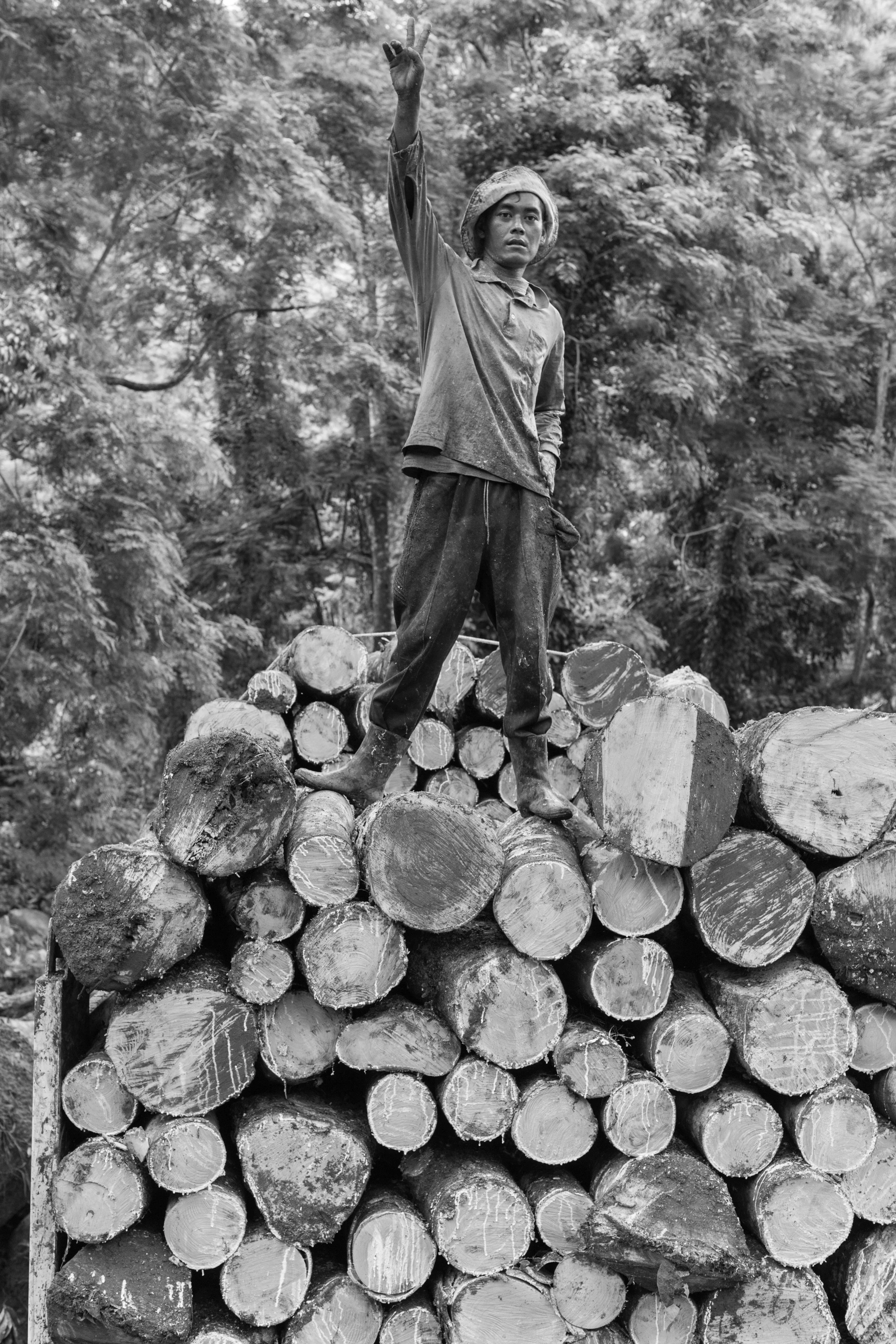

Burmese worker atop loaded truck and unbowed by the hard work, southern Thailand, 2015

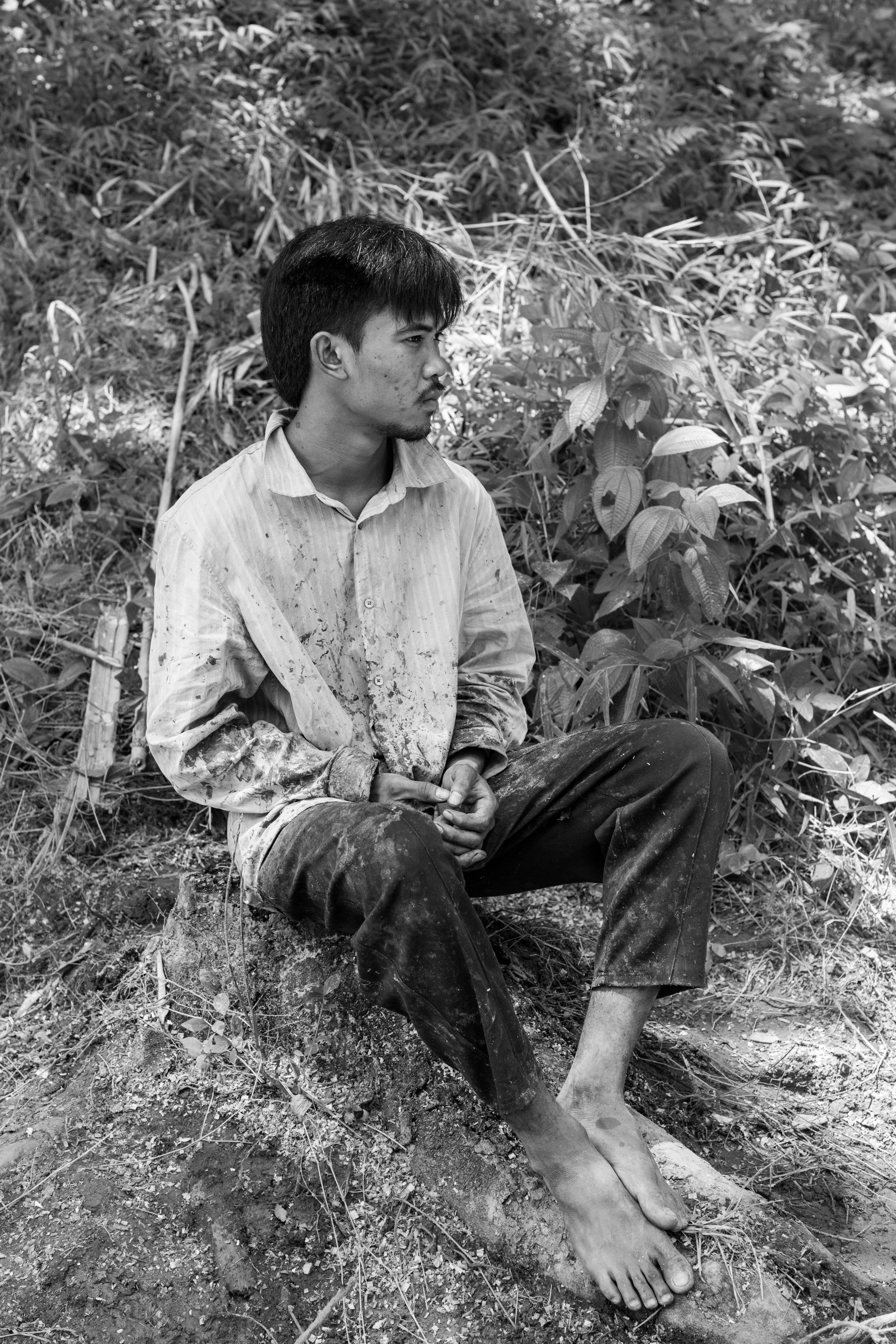

Young man taking a break from work loading log transport truck, southern Thailand, 2015

Middle-aged man taking a break from logging work, southern Thailand, 2015

Handler speaking with an elephant during water and rest break, southern Thailand, 2015

Elephant spraying itself during a rest break, southern Thailand, 2015

Elephants wading and submerging during a rest break, southern Thailand, 2015

Elephants leaving river to return to afternoon work, southern Thailand, 2015

Elephant awaiting return to its home at owner's residence, southern Thailand, 2015

Elephant climbing into truck bed for transport home, southern Thailand, 2015

Elephant and handler heading home after a day's work, southern Thailand, 2015

Rubber wood transport truck dumping parawood logs at parawood mill, southern Thailand, 2015

Front loader bringing some order to dumped logs at parawood mill, southern Thailand, 2015

Logs ready for milling, southern Thailand, 2015

Larger logs framing back of a work area, parawood mill, southern Thailand, 2015

Feeding a small log into bandsaw, parawood mill, southern Thailand, 2015

Cutting fluid at hand while removing bark edge, parawood mill, southern Thailand, 2015

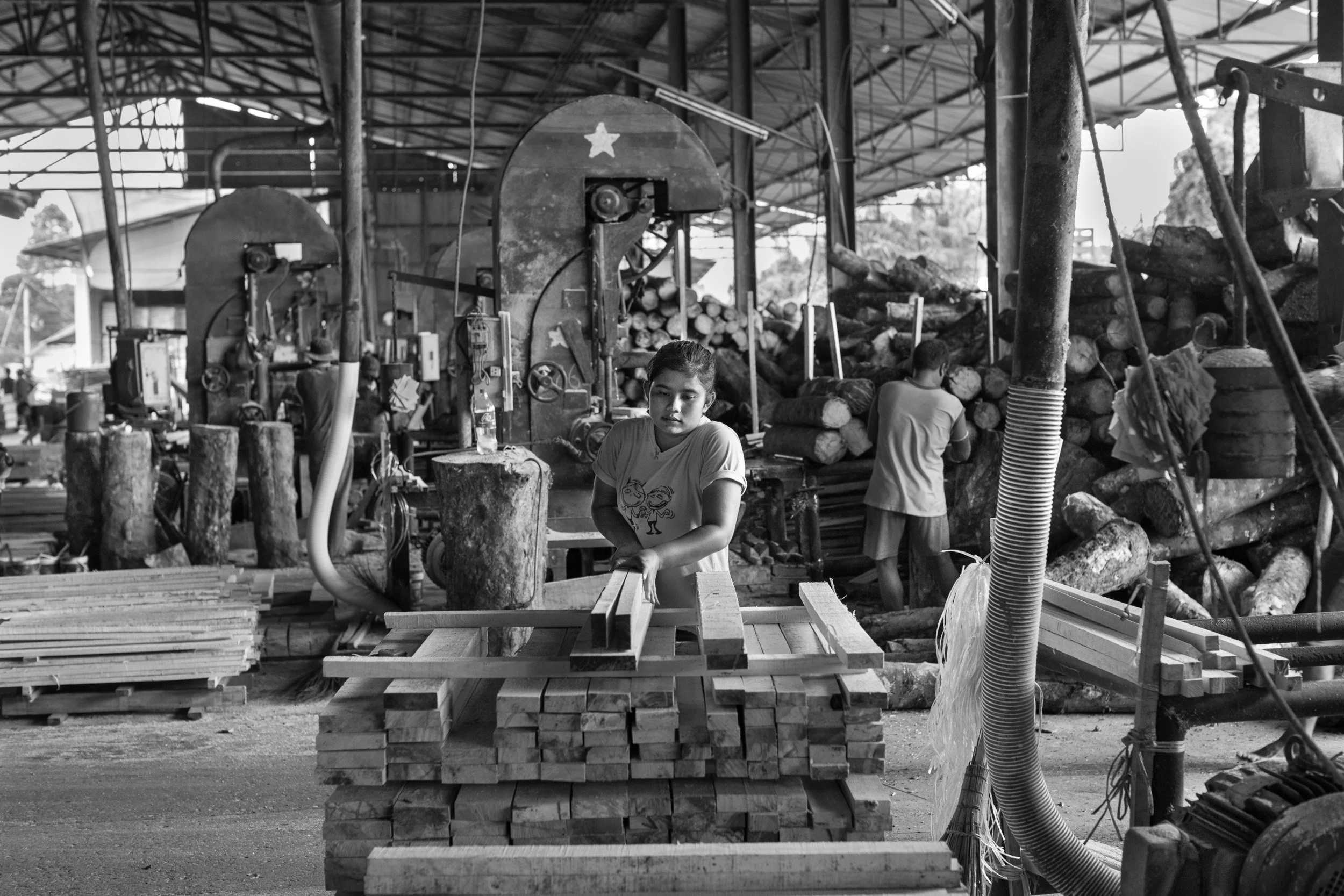

Girl carrying milled boards, parawood mill, southern Thailand, 2015

Girl stacking milled boards, parawood mill, southern Thailand, 2015

Squaring a large log, parawood mill, southern Thailand, 2015

Reducing a large log to board stock, parawood mill, southern Thailand, 2015

Woman resting on a stack of milled boards, parawood mill, southern Thailand, 2015

Changing band saw blade , parawood mill, southern Thailand, 2015

Band saw blade sharpening room, parawood mill, southern Thailand, 2015

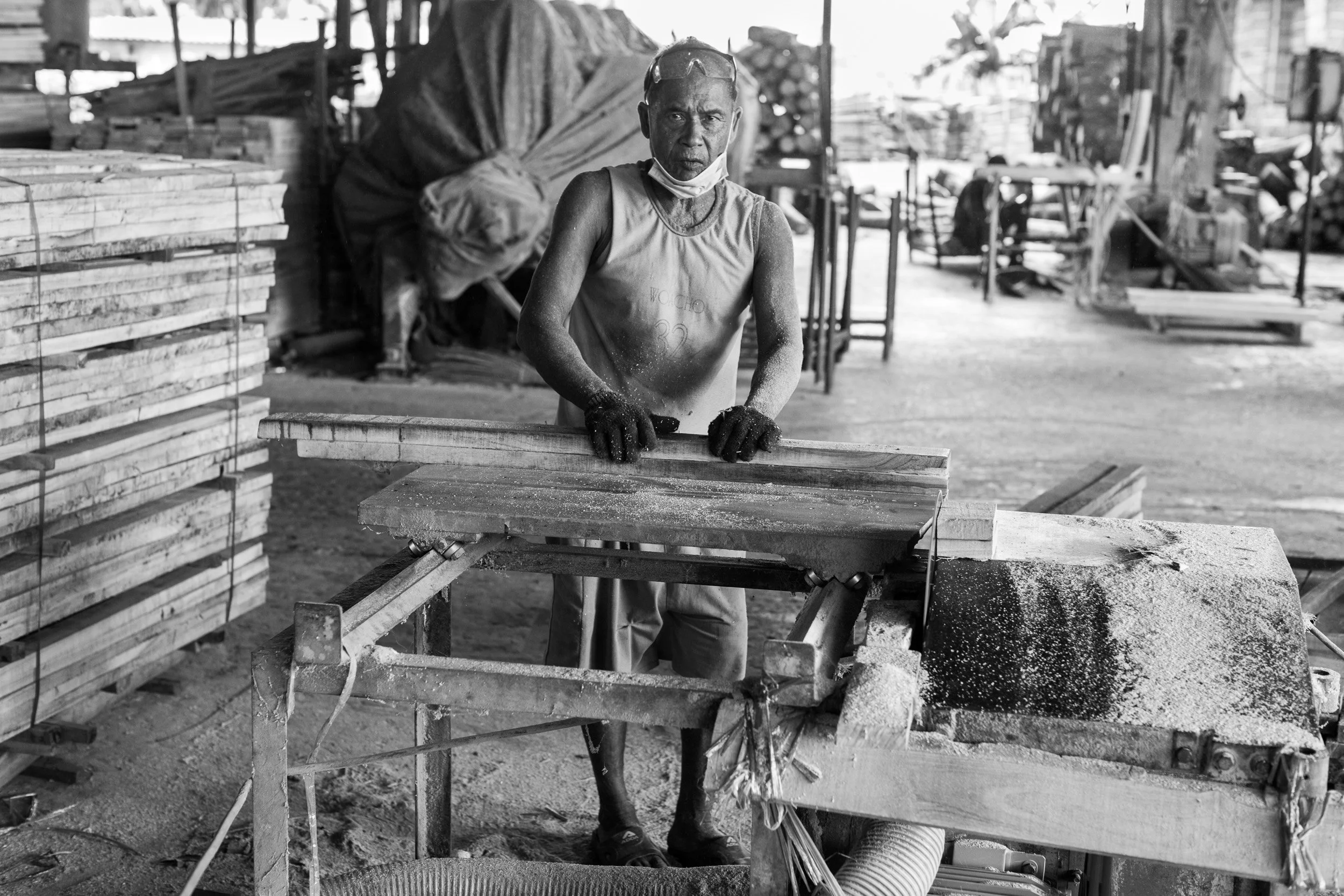

Cross cutting for wooden blocks, parawood mill, southern Thailand, 2015

Young girl bagging wooden blocks, parawood mill, southern Thailand, 2015

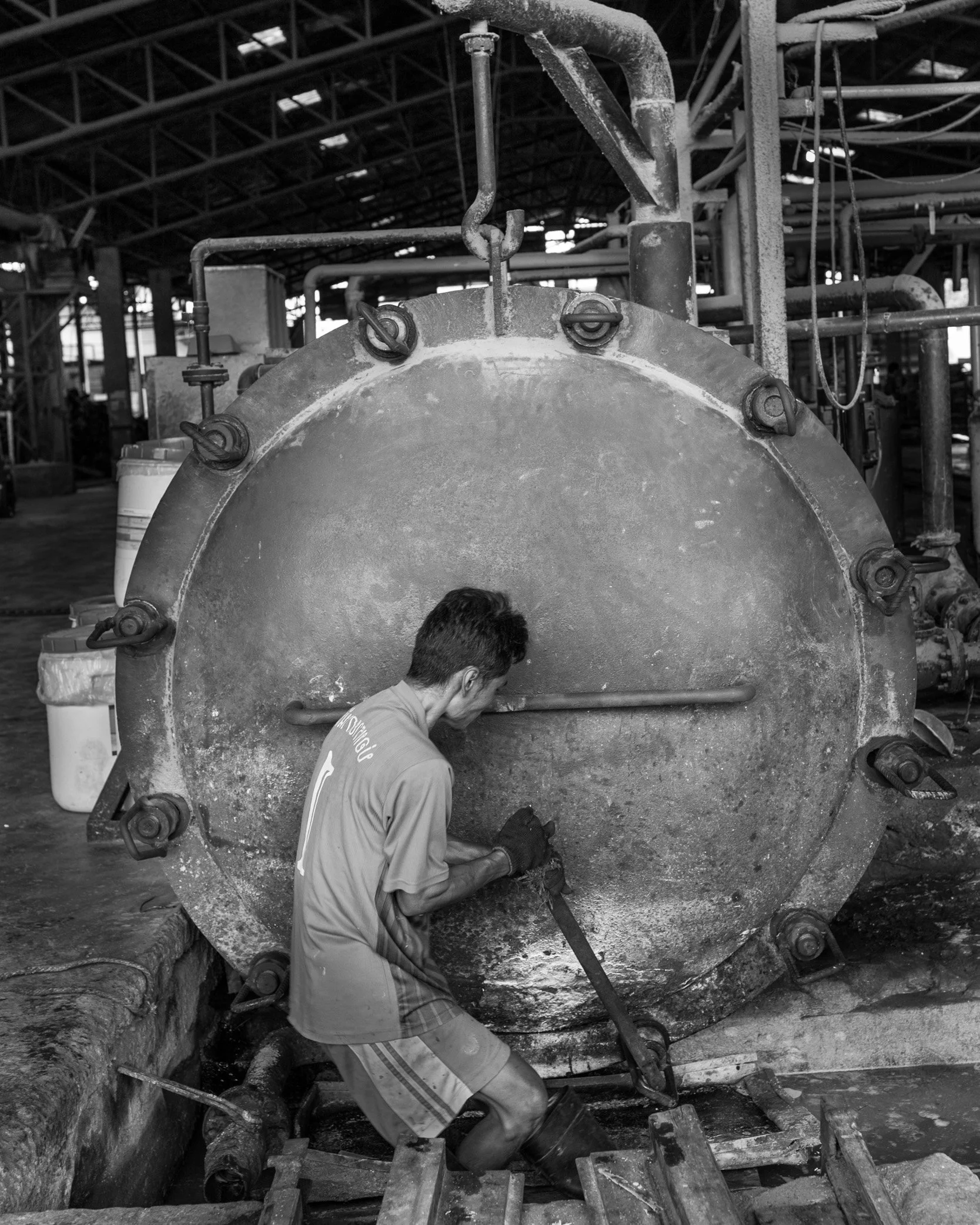

Securing wood pressure treatment chamber, parawood mill, southern Thailand, 2015

Removing wood from chamber following treatment under pressure, parawood mill, southern Thailand, 2015

Forklift stacking pallets of finished boards, parawood mill, southern Thailand, 2015

View of the work floor, parawood mill, southern Thailand, 2015

Sawdust pile from dust recovery system, parawood mill, southern Thailand, 2015

Taking a break from work, parawood mill, southern Thailand, 2015

Workers' table with Buddhist year calendar and photograph of much-loved King Rama IX, parawood mill, southern Thailand, 2015

Clock and information board, parawood mill, southern Thailand, 2015

Young resident migrant worker cleaned up and resting at the end of his work shift, parawood mill, southern Thailand, 2015